Graph algorithms

Download exercises zip

(before editing read whole introduction section 0.x)

What to do

unzip exercises in a folder, you should get something like this:

graph-algos

graph.py

graph_sol.py

jupman.py

sciprog.py

graph-algos.ipynb

open the editor of your choice (for example Visual Studio Code, Spyder or PyCharme), you will edit the files ending in

.pyfilesGo on reading this notebook, and follow instuctions inside.

Introduction

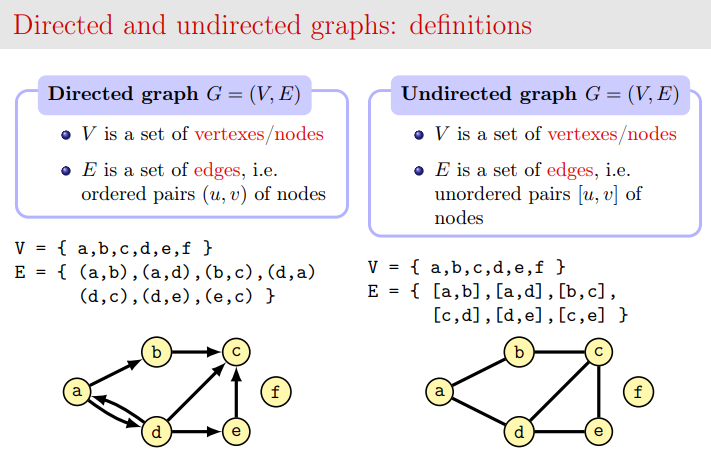

0.1 Graph theory

In short, a graph is a set of vertices linked by edges.

Longer version:

Python DS book - Graphs chapter

In particular, see Vocabulary and definitions

Credits: Slides by Alberto Montresor

0.2 Directed graphs

In this worksheet we are going to use so called Directed Graphs (DiGraph for brevity), that is, graphs with directed edges: each edge can be pictured as an arrow linking source node a to target node b. With such an arrow, you can go from a to b but you cannot go from b to a unless there is another edge in the reverse direction.

DiGraphfor us can also have no edges or no verteces at all.Verteces for us can be anything, strings like ‘abc’, numbers like

3, etcIn our model, edges simply link vertices and have no weights

DiGraphis represented as an adjacency list, mapping each vertex to the verteces it is linked to.

QUESTION: is DiGraph model good for dense or sparse graphs?

0.3 Serious graphs

In this worksheet we follow the Do It Yourself methodology and create graph classes from scratch for didactical purposes. Of course, in Python world you have alread nice libraries entirely devoted to graphs like networkx, you can also use them for visualizating graphs. If you have huge graphs to process you might consider big data tools like Spark GraphX which is programmable in Python.

0.4 Code skeleton

First off, download the exercises zip and look at the files:

graph.py: the exercise to editgraph_test.py: the tests to run. Do not modify this file.

Before starting to implement methods in DiGraph class, read all the following sub sections (starting with ‘0.x’)

0.5 Building graphs

IMPORTANT: All the functions in section 0 are already provided and you don’t need to implement them !

For now, open a Python 3 interpreter and try out the graph_sol module :

[2]:

from graph_sol import *

0.5.1 Building basics

Let’s look at the constructor __init__ and add_vertex. They are already provided and you don’t need to implement it:

class DiGraph:

def __init__(self):

# The class just holds the dictionary _edges: as keys it has the verteces, and

# to each vertex associates a list with the verteces it is linked to.

self._edges = {}

def add_vertex(self, vertex):

""" Adds vertex to the DiGraph. A vertex can be any object.

If the vertex already exist, does nothing.

"""

if vertex not in self._edges:

self._edges[vertex] = []

You will see that inside it just initializes _edges. So the only way to create a DiGraph is with a call like

[3]:

g = DiGraph()

DiGraph provides an __str__ method to have a nice printout:

[4]:

print(g)

DiGraph()

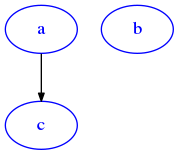

To draw a DiGraph, you can use draw_dig from sciprog module - in this case draw nothing as the graph is empty:

[5]:

from sciprog import draw_dig

draw_dig(g)

You can add then vertices to the graph like so:

[6]:

g.add_vertex('a')

g.add_vertex('b')

g.add_vertex('c')

[7]:

print(g)

a: []

b: []

c: []

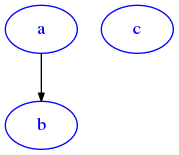

To draw a DiGraph, you can use draw_dig from sciprog module:

[8]:

from sciprog import draw_dig

draw_dig(g)

Adding a vertex twice does nothing:

[9]:

g.add_vertex('a')

print(g)

a: []

b: []

c: []

Once you added the verteces, you can start adding directed edges among them with the method add_edge:

def add_edge(self, vertex1, vertex2):

""" Adds an edge to the graph, from vertex1 to vertex2

If verteces don't exist, raises a ValueError.

If there is already such an edge, exits silently.

"""

if not vertex1 in self._edges:

raise ValueError("Couldn't find source vertex:" + str(vertex1))

if not vertex2 in self._edges:

raise ValueError("Couldn't find target vertex:" + str(vertex2))

if not vertex2 in self._edges[vertex1]:

self._edges[vertex1].append(vertex2)

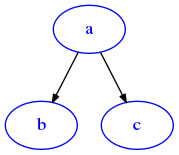

[10]:

g.add_edge('a', 'c')

print(g)

a: ['c']

b: []

c: []

[11]:

draw_dig(g)

[12]:

g.add_edge('a', 'b')

print(g)

a: ['c', 'b']

b: []

c: []

[13]:

draw_dig(g)

Adding an edge twice makes no difference:

[14]:

g.add_edge('a', 'b')

print(g)

a: ['c', 'b']

b: []

c: []

Notice a DiGraph can have self-loops too (also called caps):

[15]:

g.add_edge('b', 'b')

print(g)

a: ['c', 'b']

b: ['b']

c: []

[16]:

draw_dig(g)

0.5.2 dig()

dig() is a shortcut to build graphs, it is already provided and you don’t need to implement it.

USE IT ONLY WHEN TESTING, *NOT* IN THE ``DiGraph`` CLASS CODE !!!!

First of all, remember to import it from graph_test package:

[17]:

from graph_test import dig

With empty dict prints the empty graph:

[18]:

print(dig({}))

DiGraph()

To build more complex graphs, provide a dictionary with pairs source vertex / target verteces list like in the following examples:

[19]:

print(dig({'a':['b','c']}))

a: ['b', 'c']

b: []

c: []

[20]:

print(dig({'a': ['b','c'],

'b': ['b'],

'c': ['a']}))

a: ['b', 'c']

b: ['b']

c: ['a']

0.6 Equality

Graphs for us are equal irrespectively of the order in which elements in adjacency lists are specified. So for example these two graphs will be considered equal:

[21]:

dig({'a': ['c', 'b']}) == dig({'a': ['b', 'c']})

[21]:

True

0.7 Basic querying

There are some provided methods to query the DiGraph: adj, verteces, is_empty

0.7.1 adj

To obtain the edges, you can use the method adj(self, vertex). It is already provided and you don’t need to implement it:

def adj(self, vertex):

""" Returns the verteces adjacent to vertex.

NOTE: verteces are returned in a NEW list.

Modifying the list will have NO effect on the graph!

"""

if not vertex in self._edges:

raise ValueError("Couldn't find a vertex " + str(vertex))

return self._edges[vertex][:]

[22]:

lst = dig({'a': ['b', 'c'],

'b': ['c']}).adj('a')

print(lst)

['b', 'c']

Let’s check we actually get back a new list (so modifying the old one won’t change the graph):

[23]:

lst.append('d')

print(lst)

['b', 'c', 'd']

[24]:

print(g.adj('a'))

['c', 'b']

NOTE: This technique of giving back copies is also called defensive copying: it prevents users from modifying the internal data structures of a class instance in an uncontrolled manner. For example, if we allowed them direct access to the internal verteces list, they could add duplicate edges, which we don’t allow in our model. If instead we only allow users to add edges by calling add_edge, we are sure the constraints for our model will always remain satisfied.

0.7.2 is_empty()

We can check if a DiGraph is empty. It is already provided and you don’t need to implement it:

def is_empty(self):

""" A DiGraph for us is empty if it has no verteces and no edges """

return len(self._edges) == 0

[25]:

print(dig({}).is_empty())

True

[26]:

print(dig({'a':[]}).is_empty())

False

0.7.3 verteces()

To obtain the verteces, you can use the function verteces. (NOTE for Italians: method is called verteces, with two es !!!). It is already provided and you don’t need to implement it:

def verteces(self):

""" Returns a view of the graph verteces. Verteces can be any immutable object. """

return set(self._edges.keys())

[27]:

g = dig({'a': ['c', 'b'],

'b': ['c']})

print(g.verteces())

dict_keys(['a', 'c', 'b'])

Notice it returns a set, as verteces are stored as keys in a dictionary, so they are not supposed to be in any particular order. When you print the whole graph you see them vertically ordered though, for clarity purposes:

[28]:

print(g)

a: ['c', 'b']

b: ['c']

c: []

Verteces in the edges list are instead stored and displayed in the order in which they were inserted.

0.8 Blow up your computer

Try to call the already implemented function graph_test.gen_graphs with small numbers for n, like 1, 2 , 3 , 4 …. Just with 2 we get back a lot of graphs:

def gen_graphs(n):

""" Returns a list with all the possible 2^(n^2) graphs of size n

Verteces will be identified with numbers from 1 to n

"""

[29]:

from graph_test import gen_graphs

print(gen_graphs(2))

[

1: []

2: []

,

1: []

2: [2]

,

1: []

2: [1]

,

1: []

2: [1, 2]

,

1: [2]

2: []

,

1: [2]

2: [2]

,

1: [2]

2: [1]

,

1: [2]

2: [1, 2]

,

1: [1]

2: []

,

1: [1]

2: [2]

,

1: [1]

2: [1]

,

1: [1]

2: [1, 2]

,

1: [1, 2]

2: []

,

1: [1, 2]

2: [2]

,

1: [1, 2]

2: [1]

,

1: [1, 2]

2: [1, 2]

]

QUESTION: What happens if you call gen_graphs(10) ? How many graphs do you get back ?

1. Implement building

Enough for talking! Let’s implement building graphs.

1.1 has_edge

Implement this method in DiGraph:

def has_edge(self, source, target):

""" Returns True if there is an edge between source vertex and target vertex.

Otherwise returns False.

If either source, target or both verteces don't exist raises a ValueError

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.HasEdgeTest

1.2 full_graph

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def full_graph(verteces):

""" Returns a DiGraph which is a full graph with provided verteces list.

In a full graph all verteces link to all other verteces (including themselves!).

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.FullGraphTest

1.3 dag

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def dag(verteces):

""" Returns a DiGraph which is DAG (Directed Acyclic Graph) made out of provided verteces list

Provided list is intended to be in topological order.

NOTE: a DAG is ACYCLIC, so caps (self-loops) are not allowed !!

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.DagTest

1.4 list_graph

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def list_graph(n):

""" Return a graph of n verteces displaced like a

monodirectional list: 1 -> 2 -> 3 -> ... -> n

Each vertex is a number i, 1 <= i <= n and has only one edge connecting it

to the following one in the sequence

If n = 0, return the empty graph.

if n < 0, raises a ValueError.

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.ListGraphTest

1.5 star_graph

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def star_graph(n):

""" Returns graph which is a star with n nodes

First node is the center of the star and it is labeled with 1. This node is linked

to all the others. For example, for n=4 you would have a graph like this:

3

^

|

2 <- 1 -> 4

If n = 0, the empty graph is returned

If n < 0, raises a ValueError

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.StarGraphTest

1.6 odd_line

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def odd_line(n):

""" Returns a DiGraph with n verteces, displaced like a line of odd numbers

Each vertex is an odd number i, for 1 <= i < 2n. For example, for

n=4 verteces are displaced like this:

1 -> 3 -> 5 -> 7

For n = 0, return the empty graph

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.OddLineTest

Example usage:

[30]:

odd_line(0)

[30]:

DiGraph()

[31]:

odd_line(1)

[31]:

1: []

[32]:

odd_line(2)

[32]:

1: [3]

3: []

[33]:

odd_line(3)

[33]:

1: [3]

3: [5]

5: []

[34]:

odd_line(4)

[34]:

1: [3]

3: [5]

5: [7]

7: []

1.7 even_line

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def even_line(n):

""" Returns a DiGraph with n verteces, displaced like a line of even numbers

Each vertex is an even number i, for 2 <= i <= 2n. For example, for

n=4 verteces are displaced like this:

2 <- 4 <- 6 <- 8

For n = 0, return the empty graph

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.EvenLineTest

Example usage:

[35]:

even_line(0)

[35]:

DiGraph()

[36]:

even_line(1)

[36]:

2: []

[37]:

even_line(2)

[37]:

2: []

4: [2]

[38]:

even_line(3)

[38]:

2: []

4: [2]

6: [4]

1.8 quads

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def quads(n):

""" Returns a DiGraph with 2n verteces, displaced like a strip of quads.

Each vertex is a number i, 1 <= i <= 2n.

For example, for n = 4, verteces are displaced like this:

1 -> 3 -> 5 -> 7

^ | ^ |

| ; | ;

2 <- 4 <- 6 <- 8

where

^ |

| represents an upward arrow, while ; represents a downward arrow

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.QuadsTest

Example usage:

[39]:

quads(0)

[39]:

DiGraph()

[40]:

quads(1)

[40]:

1: []

2: [1]

[41]:

quads(2)

[41]:

1: [3]

2: [1]

3: [4]

4: [2]

[42]:

quads(3)

[42]:

1: [3]

2: [1]

3: [5, 4]

4: [2]

5: []

6: [4, 5]

[43]:

quads(4)

[43]:

1: [3]

2: [1]

3: [5, 4]

4: [2]

5: [7]

6: [4, 5]

7: [8]

8: [6]

1.9 pie

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def pie(n):

"""

Returns a DiGraph with n+1 verteces, displaced like a polygon with a perimeter

of n verteces progressively numbered from 1 to n.

A central vertex numbered zero has outgoing edges to all other verteces.

For n = 0, return the empty graph.

For n = 1, return vertex zero connected to node 1, and node 1 has a self-loop.

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.PieTest

Example usage:

For n=5, the function creates this graph:

[44]:

pie(5)

[44]:

0: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

1: [2]

2: [3]

3: [4]

4: [5]

5: [1]

Degenerate cases:

[45]:

pie(0)

[45]:

DiGraph()

[46]:

pie(1)

[46]:

0: [1]

1: [1]

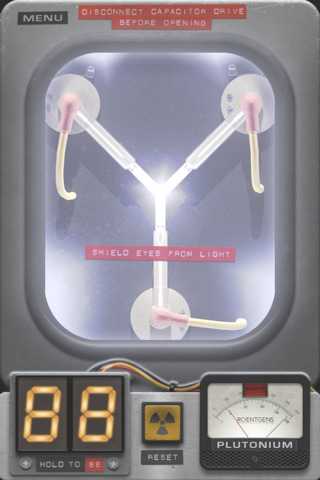

1.10 Flux Capacitor

A Flux Capacitor is a plutonium-powered device that enables time travelling. During the 80s it was installed on a Delorean car and successfully used to ride humans back and forth across centuries:

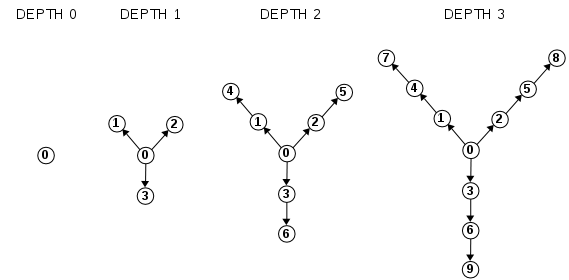

In this exercise you will build a Flux Capacitor model as a Y-shaped DiGraph, created according to a parameter depth. Here you see examples at different depths:

Implement this function outside the class definition. It is not a method of DiGraph !

def flux(depth):

""" Returns a DiGraph with 1 + (d * 3) numbered verteces displaced like a Flux Capacitor:

- from a central node numbered 0, three branches depart

- all edges are directed outward

- on each branch there are 'depth' verteces.

- if depth < 0, raises a ValueError

For example, for depth=2 we get the following graph (suppose arrows point outward):

4 5

\ /

1 2

\ /

0

|

3

|

6

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.FluxTest

Example usage:

[47]:

flux(0)

[47]:

0: []

[48]:

flux(1)

[48]:

0: [1, 2, 3]

1: []

2: []

3: []

[49]:

flux(2)

[49]:

0: [1, 2, 3]

1: [4]

2: [5]

3: [6]

4: []

5: []

6: []

[50]:

flux(3)

[50]:

0: [1, 2, 3]

1: [4]

2: [5]

3: [6]

4: [7]

5: [8]

6: [9]

7: []

8: []

9: []

2. Manipulate graphs

You will now implement some methods to manipulate graphs.

2.1 remove_vertex

def remove_vertex(self, vertex):

""" Removes the provided vertex and returns it

If the vertex is not found, raises a LookupError

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.RemoveVertexTest

2.2 transpose

def transpose(self):

""" Reverses the direction of all the edges

- MUST perform in O(|V|+|E|)

Note in adjacency lists model we suppose there are only few edges per node,

so if you end up with an algorithm which is O(|V|^2) you are ending up with a

complexity usually reserved for matrix representations !!

NOTE: this method changes in-place the graph: does **not** create a new instance

and does *not* return anything !!

NOTE: To implement it *avoid* modifying the existing _edges dictionary (would

probably more problems than anything else).

Instead, create a new dictionary, fill it with the required

verteces and edges ad then set _edges to point to the new dictionary.

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.TransposeTest

2.3 has_self_loops

def has_self_loops(self):

""" Returns True if the graph has any self loop (a.k.a. cap), False otherwise """

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.HasSelfLoopsTest

2.4 remove_self_loops

def remove_self_loops(self):

""" Removes all of the self-loops edges (a.k.a. caps)

NOTE: Removes just the edges, not the verteces!

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.RemoveSelfLoopsTest

2.5 undir

def undir(self):

""" Return a *NEW* undirected version of this graph, that is, if an edge a->b exists in this graph,

the returned graph must also have both edges a->b and b->a

*DO NOT* modify the current graph, just return an entirely new one.

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.UndirTest

3. Query graphs

You can query graphs the Do it yourself way with Depth First Search (DFS) or Breadth First Search (BFS).

Let’s make a simple example:

[51]:

g = dig({'a': ['a','b', 'c'],

'b': ['c'],

'd': ['e']})

from sciprog import draw_dig

draw_dig(g)

[52]:

g.dfs('a')

DEBUG: Stack is: ['a']

DEBUG: popping from stack: a

DEBUG: not yet visited

DEBUG: Scheduling for visit: a

DEBUG: Scheduling for visit: b

DEBUG: Scheduling for visit: c

DEBUG: Stack is : ['a', 'b', 'c']

DEBUG: popping from stack: c

DEBUG: not yet visited

DEBUG: Stack is : ['a', 'b']

DEBUG: popping from stack: b

DEBUG: not yet visited

DEBUG: Scheduling for visit: c

DEBUG: Stack is : ['a', 'c']

DEBUG: popping from stack: c

DEBUG: already visited!

DEBUG: popping from stack: a

DEBUG: already visited!

Compare it wirh the example for the bfs :

[53]:

draw_dig(g)

[54]:

g.bfs('a')

DEBUG: Removed from queue: a

DEBUG: Found neighbor: a

DEBUG: already visited

DEBUG: Found neighbor: b

DEBUG: not yet visited, enqueueing ..

DEBUG: Found neighbor: c

DEBUG: not yet visited, enqueueing ..

DEBUG: Queue is: ['b', 'c']

DEBUG: Removed from queue: b

DEBUG: Found neighbor: c

DEBUG: already visited

DEBUG: Queue is: ['c']

DEBUG: Removed from queue: c

DEBUG: Queue is: []

Predictably, results are different.

3.1 distances()

Implement this method of DiGraph:

def distances(self, source):

"""

Returns a dictionary where the keys are verteces, and each vertex v is associated

to the *minimal* distance in number of edges required to go from the source

vertex to vertex v. If node is unreachable, the distance will be -1

Source has distance zero from itself

Verteces immediately connected to source have distance one.

- if source is not a vertex, raises an LookupError

- MUST execute in O(|V| + |E|)

- HINT: implement this using bfs search.

"""

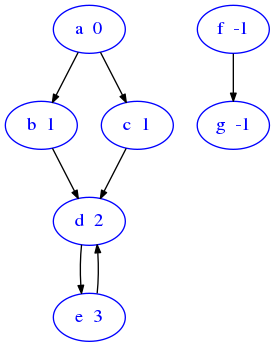

If you look at the following graph, you can see an example of the distances to associate to each vertex, supposing that the source is a. Note that a iself is at distance zero from itself and also that unreachable nodes like f and g will be at distance -1

[55]:

import sciprog

sciprog.draw_nx(sciprog.show_distances())

distances('a') called on this graph would return a map like this:

{

'a':0,

'b':1,

'c':1,

'd':2,

'e':3,

'f':-1,

'g':-1,

}

3.2 equidistances()

Implement this method of DiGraph:

def equidistances(self, va, vb):

""" RETURN a dictionary holding the nodes which

are equidistant from input verteces va and vb.

The dictionary values will be the distances of the nodes.

- if va or vb are not present in the graph, raises LookupError

- MUST execute in O(|V| + |E|)

- HINT: To implement this, you can use the previously defined distances() method

"""

Example:

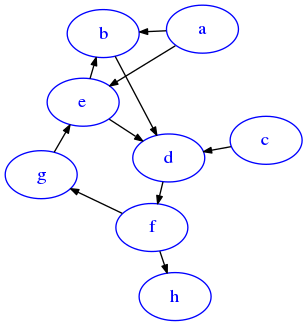

[56]:

G = dig({'a': ['b','e'],

'b': ['d'],

'c': ['d'],

'd': ['f'],

'e': ['d','b'],

'f': ['g','h'],

'g': ['e']})

draw_dig(G, options={'graph':{'layout':'fdp', 'start':'random10'}})

Consider a and g, they both:

can reach

ein one stepcan reach

din two stepscan reach

fin three stepscan reach

hin four stepscis unreachable by bothaandg,so it won’t be present in the outputbis reached fromain one step, and fromgin two steps, so it won’t be included in the output

[57]:

G.equidistances('a','g')

[57]:

{'e': 1, 'd': 2, 'f': 3, 'h': 4}

3.3 Play with dfs and bfs

Create small graphs (like linked lists a->b->c, triangles, mini-full graphs, trees - you can also use the functions you defined to create graphs like full_graph, dag, list_graph, star_graph) and try to predict the visit sequence (verteces order, with discovery and finish times) you would have running a dfs or bfs. Then write tests that assert you actually get those sequences when running provided dfs and bfs

3.4 Exits graph

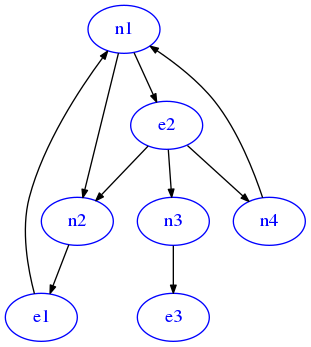

There is a place nearby Trento called Silent Hill, where people always study and do little else. Unfortunately, one day an unethical biotech AI experiment goes wrong and a buggy cyborg is left free to roam in the building. To avoid panic, you are quickly asked to devise an evacuation plan. The place is a well known labyrinth, with endless corridors also looping into cycles. But you know you can model this network as a digraph, and decide to represent crossings as nodes. When a crossing has a

door to leave the building, its label starts with letter e, while when there is no such door the label starts with letter n.

In the example below, there are three exits e1, e2, and e3. Given a node, say n1, you want to tell the crowd in that node the shortest paths leading to the three exits. To avoid congestion, one third of the crowd may be told to go to e2, one third to reach e1 and the remaining third will go to e3 even if they are farther than e2.

In Python terms, we would like to obtain a dictionary of paths like the following, where as keys we have the exits and as values the shortest sequence of nodes from n1 leading to that exit

{

'e1': ['n1', 'n2', 'e1'],

'e2': ['n1', 'e2'],

'e3': ['n1', 'e2', 'n3', 'e3']

}

[58]:

from sciprog import draw_dig

from graph_sol import *

from graph_test import dig

[59]:

G = dig({'n1':['n2','e2'],

'n2':['e1'],

'e1':['n1'],

'e2':['n2','n3', 'n4'],

'n3':['e3'],

'n4':['n1']})

draw_dig(G)

You will solve the exercise in steps, so open exits_sol.py and proceed reading the following points.

3.4.1 Exits graph cp

Implement this method

def cp(self, source):

""" Performs a BFS search starting from provided node label source and

RETURN a dictionary of nodes representing the visit tree in the

child-to-parent format, that is, each key is a node label and as value

has the node label from which it was discovered for the first time

So if node "n2" was discovered for the first time while

inspecting the neighbors of "n1", then in the output dictionary there

will be the pair "n2":"n1".

The source node will have None as parent, so if source is "n1" in the

output dictionary there will be the pair "n1": None

- if source is not found, raises LookupError

- MUST execute in O(|V| + |E|)

- NOTE: This method must *NOT* distinguish between exits

and normal nodes, in the tests we label them n1, e1 etc just

because we will reuse in next exercise

- NOTE: You are allowed to put debug prints, but the only thing that

matters for the evaluation and tests to pass is the returned

dictionary

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.CpTest

Example:

[60]:

G.cp('n1')

DEBUG: Removed from queue: n1

DEBUG: Found neighbor: n2

DEBUG: not yet visited, enqueueing ..

DEBUG: Found neighbor: e2

DEBUG: not yet visited, enqueueing ..

DEBUG: Queue is: ['n2', 'e2']

DEBUG: Removed from queue: n2

DEBUG: Found neighbor: e1

DEBUG: not yet visited, enqueueing ..

DEBUG: Queue is: ['e2', 'e1']

DEBUG: Removed from queue: e2

DEBUG: Found neighbor: n2

DEBUG: already visited

DEBUG: Found neighbor: n3

DEBUG: not yet visited, enqueueing ..

DEBUG: Found neighbor: n4

DEBUG: not yet visited, enqueueing ..

DEBUG: Queue is: ['e1', 'n3', 'n4']

DEBUG: Removed from queue: e1

DEBUG: Found neighbor: n1

DEBUG: already visited

DEBUG: Queue is: ['n3', 'n4']

DEBUG: Removed from queue: n3

DEBUG: Found neighbor: e3

DEBUG: not yet visited, enqueueing ..

DEBUG: Queue is: ['n4', 'e3']

DEBUG: Removed from queue: n4

DEBUG: Found neighbor: n1

DEBUG: already visited

DEBUG: Queue is: ['e3']

DEBUG: Removed from queue: e3

DEBUG: Queue is: []

[60]:

{'n1': None,

'n2': 'n1',

'e2': 'n1',

'e1': 'n2',

'n3': 'e2',

'n4': 'e2',

'e3': 'n3'}

Basically, the dictionary above represents this visit tree:

n1

/ \

n2 e2

\ / \

e1 n3 n4

|

e3

3.4.2 Exit graph exits

Implement this function. NOTE: the function is external to class DiGraph.

def exits(cp):

"""

INPUT: a dictionary of nodes representing a visit tree in the

child-to-parent format, that is, each key is a node label and

as value has its parent as a node label. The root has

associated None as parent.

OUTPUT: a dictionary mapping node labels of exits to a list

of node labels representing the the shortest path from

the root to the exit (root and exit included)

- MUST execute in O(|V| + |E|)

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.ExitsTest

Example:

[61]:

# as example we can use the same dictionary outputted by the cp call in the previous exercise

visit_cp = { 'e1': 'n2',

'e2': 'n1',

'e3': 'n3',

'n1': None,

'n2': 'n1',

'n3': 'e2',

'n4': 'e2'

}

exits(visit_cp)

[61]:

{'e1': ['n1', 'n2', 'e1'], 'e2': ['n1', 'e2'], 'e3': ['n1', 'e2', 'n3', 'e3']}

3.5 connected components

Implement cc:

def cc(self):

""" Finds the connected components of the graph, returning a dict object

which associates to the verteces the corresponding connected component

number id, where 1 <= id <= |V|

IMPORTANT: ASSUMES THE GRAPH IS UNDIRECTED !

ON DIRECTED GRAPHS, THE RESULT IS UNPREDICTABLE !

To develop this function, implement also ccdfs

HINT: store 'counter' as field in Visit object

"""

Which in turn uses the FUNCTION ccdfs, also to implement INSIDE the method cc:

def ccdfs(counter, source, ids):

"""

Performs a DFS from source vertex

HINT: Copy in here the method from DFS and adapt it as needed

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.CCTest

NOTE: In tests, to keep code compact graphs are created a call to udig()

[62]:

from graph_test import udig

udig({'a': ['b'],

'c': ['d']})

[62]:

a: ['b']

b: ['a']

c: ['d']

d: ['c']

which makes sure the resulting graph is undirected as CC algorithm requires (so if there is one edge a->b there will also be another edge b->a)

3.6 has_cycle

Implement has_cycle method for directed graphs:

def has_cycle(self):

""" Return True if this directed graph has a cycle, return False otherwise.

- To develop this function, implement also has_cycle_rec(u) inside this method

- Inside has_cycle_rec, to reference variables of has_cycle you need to

declare them as nonlocal like

nonlocal clock, dt, ft

- MUST be able to also detect self-loops

"""

and also has_cycle_rec inside has_cycle:

def has_cycle_rec(u):

raise Exception("TODO IMPLEMENT ME !")

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.HasCycleTest

3.7 top_sort

Look at Luca Bianco’s slides on topological sort

Keep in mind two things:

topological sort works on DAGs, that is, Directed Acyclic Graphs

given a graph, there can be more than one valid topological sort

it works also on DAGs having disconnected components, in which case the nodes of one component can be interspersed with the nodes of other components at will, provided the order within nodes belonging to the same component is preserved.

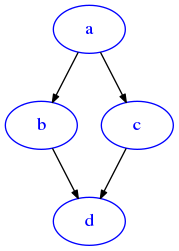

EXERCISE: Before coding, try by hand to find all the topological sorts of the following graphs. For all them, you will find the solutions listed in the tests.

[63]:

G = dig({'a':['c'],

'b':['c']})

draw_dig(G)

[64]:

G = dig({'a':['b'], 'c':[]})

draw_dig(G)

[65]:

G = dig({'a':['b'], 'c':['d']})

draw_dig(G)

[66]:

G = dig({'a':['b','c'], 'b':['d'], 'c':['d']})

draw_dig(G)

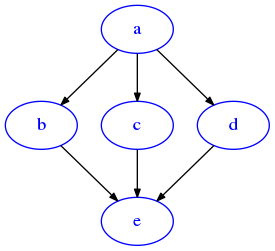

[67]:

G = dig({'a':['b','c','d'], 'b':['e'], 'c':['e'], 'd':['e']})

draw_dig(G)

[68]:

G = dig({'a':['b','c','d'], 'b':['c','d'], 'c':['d'], 'd':[]})

draw_dig(G)

Now implement this method:

def top_sort(self):

""" RETURN a topological sort of the graph. To implement this code,

feel free to adapt algorithm from theory

- implement Stack S as a list

- implement visited as a set

- NOTE: differently from Montresor code, for tests to pass

you will need to return a reversed list. Why ?

"""

Testing: python3 -m unittest graph_test.TopSortTest

Note: in tests there is the method self.assertIn(el,elements) which checks el is in elements. We use it because for a graph there a many valid topological sorts, and we want the test independent from your particular implementation .

[ ]: